Top 20 English Confusions (Grammar + Usage + Punctuation + Spelling)

We recently asked our followers on Facebook and X a simple question: “Which grammar rule has always confused you the most?” After analyzing the responses, we identified the most frequent stumbling blocks and organized them into this practical guide. Each entry below features clear examples, a concise explanation, and a specific tip to help you master the rule.

1) “I” vs “me”

grammar

Many learners aren’t sure which pronoun to choose, especially in pairs like “John and me/I”. The basic rule is simple: I is a subject; me is an object.

Tip: Remove the other person and test it: “I am ready” / “She invited me.”

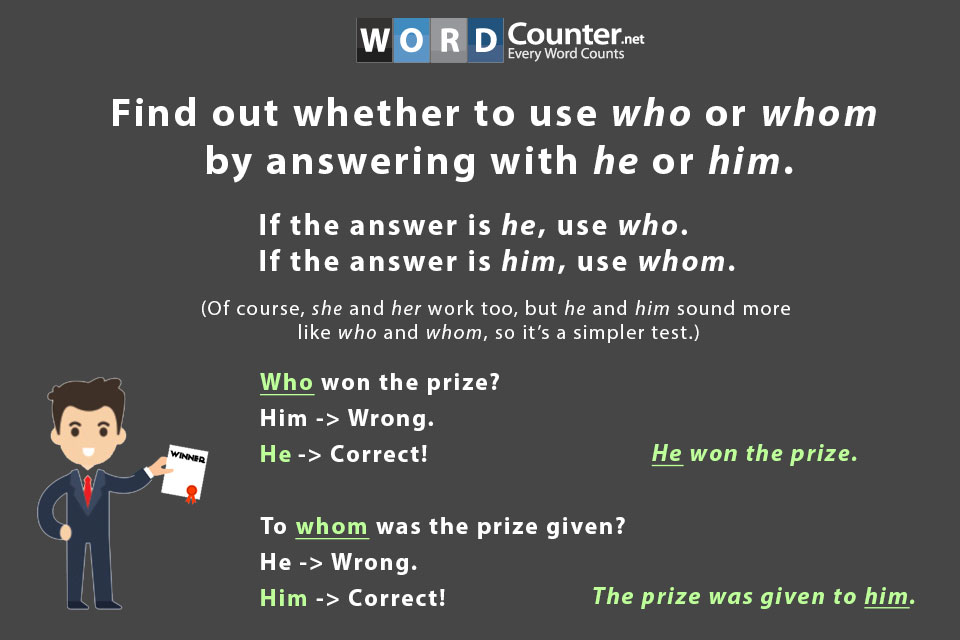

2) “Who” vs “whom”

grammar

usage

This one scares people, but it’s manageable. Who is usually a subject (does the action). Whom is usually an object (receives the action). In modern everyday English, many speakers use who instead of whom, especially in speech.

Tip: Try the “he/him” test: he → who, him → whom.

3) “A” vs “an”

pronunciation

usage

It’s not about the first letter; it’s about the first sound. Use an before a vowel sound; use a before a consonant sound.

Tip: Say the next word out loud: vowel sound → an; consonant sound → a.

4) Countable vs uncountable nouns

grammar

People often ask: “Why can I count books but not information?” Because some nouns are “mass” nouns in English. They don’t normally have a plural, and we count them using phrases like a piece of.

Small note for higher levels: a work exists in special meanings (e.g., a work of art), but work meaning “employment/effort” is usually uncountable.

Tip: If a noun feels like a “substance” (not a separate item), try some or a piece of.

5) Present perfect vs past simple

grammar

This was one of the biggest replies we got. Many learners mix these tenses because both talk about the past. The key difference is often: finished time (past simple) vs no finished time / connection to now (present perfect).

Tip: If you say when (yesterday, last year, in 2019), use past simple; if you don’t say when and it matters now, use present perfect.

6) “Since” vs “for”

grammar

Both relate to time, but they answer different questions: since = when did it start? for = how long?

Tip: Since + a starting point; for + a duration.

7) “Much” vs “many”

grammar

This confusion is very common in questions and negatives. Use many with countable plurals; use much with uncountable nouns. (And in positive sentences, a lot of is often more natural than much.)

Tip: If you can count it (1, 2, 3…), use many; if you can’t, use much.

8) “Less” vs “fewer”

usage

This is a classic. In careful English: fewer is for countable plurals, and less is for uncountable nouns. (You may see “less” with countables on signs like “10 items or less.” It’s common, but fewer is the “rule-book” choice.)

Tip: If you can count it, choose fewer; if you can’t, choose less.

9) Articles: “the” vs no article

usage

grammar

Many of you said: “I never know when to use the.” You’re not alone. A helpful simplification:

- the = something specific (we both know which one)

- no article = a general idea (in general / as a category)

Extra clarity: “go to school” often means “as a student,” while “go to the school” often means “to that building.”

Tip: Ask “Which one?” If there’s a clear answer, you probably need the.

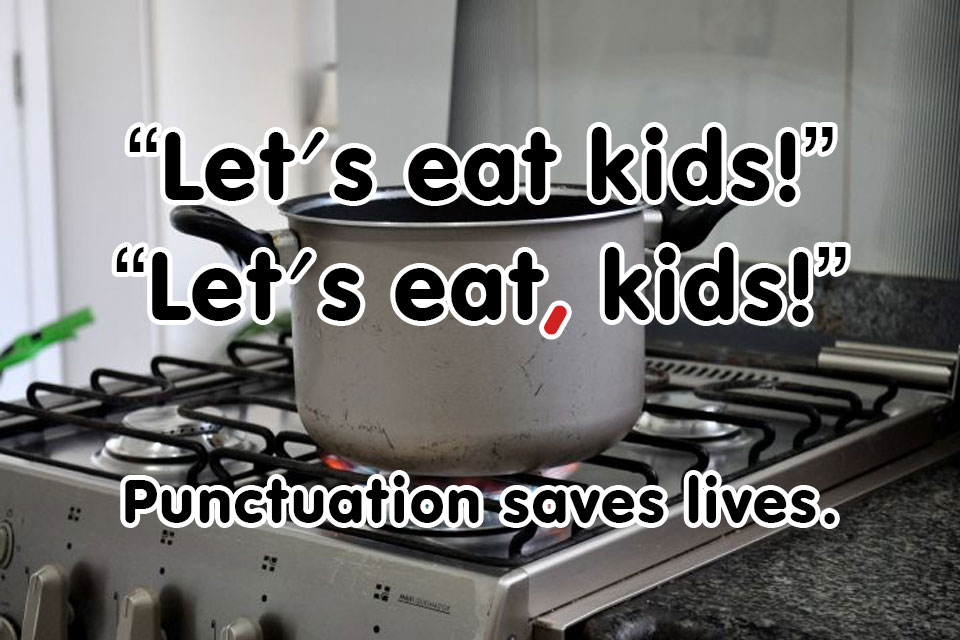

10) Apostrophes: possession vs plural

punctuation

Apostrophes cause chaos because they look small but act powerful. In general, apostrophes are for possession (belonging) or contractions (short forms), not for making plurals.

Tip: If it’s just “more than one,” don’t use an apostrophe.

11) Its vs it’s

spelling

punctuation

We saw this one a lot. Tiny difference, big meaning. It’s is a contraction; its shows possession.

Tip: If you can replace it with “it is” or “it has,” use it’s.

12) Your vs you’re

spelling

usage

Very common in fast typing. Your shows possession. You’re is a contraction of you are.

Tip: Swap in “you are.” If it works, choose you’re.

13) Their vs there vs they’re

spelling

usage

Three words that sound the same (homophones) but do different jobs. Your brain hears one sound… then your fingers choose a random spelling. It happens!

Tip: Remember the meanings: their = possession, there = place/existence, they’re = they are.

14) To vs too vs two

spelling

usage

Another homophone trio that appeared again and again. One is grammar, one is meaning, and one is just math.

Tip: Too often means “extra/also” (it has an extra “o”); two is the number; to is the basic one.

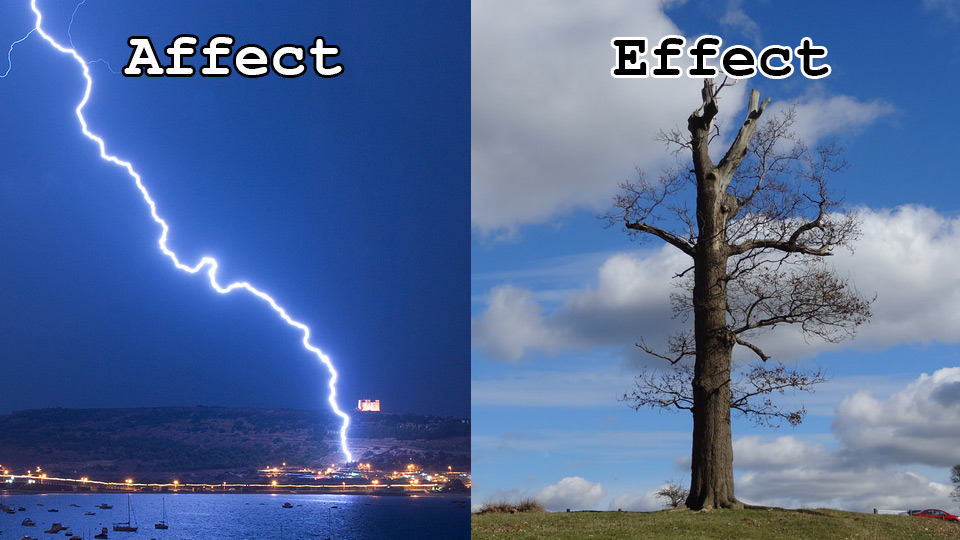

15) Affect vs effect

usage

Even advanced speakers mix these up. In most everyday cases: affect is a verb (influence), and effect is a noun (result).

Advanced note: effect can be a verb meaning “to cause to happen” (formal), but learners rarely need that first.

Tip: Quick memory: Affect = Action (verb), Effect = End result (noun).

16) Then vs than

spelling

usage

One is time. One is comparison. They are not friends. 😄

Tip: If you’re comparing, you almost always need than.

17) Comma splices (and where commas actually go)

punctuation

A common confession: “I just put commas where I breathe.” That’s understandable, but commas follow sentence structure, not breathing.

A comma splice happens when you join two complete sentences with only a comma.

Tip: If both sides can be full sentences, don’t join them with only a comma.

18) Semicolons: scary but useful

punctuation

Lots of you said semicolons feel “too advanced.” But they’re mainly used for two things: (1) connecting two related complete sentences, and (2) separating complex items in a list.

Tip: Use a semicolon to separate two related complete sentences when a period feels too strong.

19) “Who” vs “that” vs “which” (relative clauses)

grammar

Relative clauses add information about a noun. A big learner problem is choosing the word and choosing commas correctly.

- Defining (no commas): information is essential. You can often use who/that for people and which/that for things.

- Non-defining (with commas): information is extra. Use who (people) or which (things). Don’t use “that” after a comma.

Tip: If you use commas, choose who/which (not that).

20) “I could care less” vs “I couldn’t care less”

usage

This came up as a meaning confusion. Logically, “I couldn’t care less” means you care zero. “I could care less” literally suggests you care some (because it is possible to care less). You may hear both in real life, but for clear international English, teach and use the logical form.

Tip: If you mean “I don’t care at all,” say I couldn’t care less.

If English confuses you sometimes, that’s normal. The goal isn’t to never make a mistake but simply to notice patterns and improve step by step. What’s your biggest English pet peeve?