Can Single Words Be Trademarked?

Ooh! A legal minefield! Can you trademark a word? The answer is actually, “Yes!”—but not just any word. If you invented it and use it to identify your goods or services, you can. There are many examples of this, along with cases where challenges to trademarked words have succeeded.

One Big Trademark Success

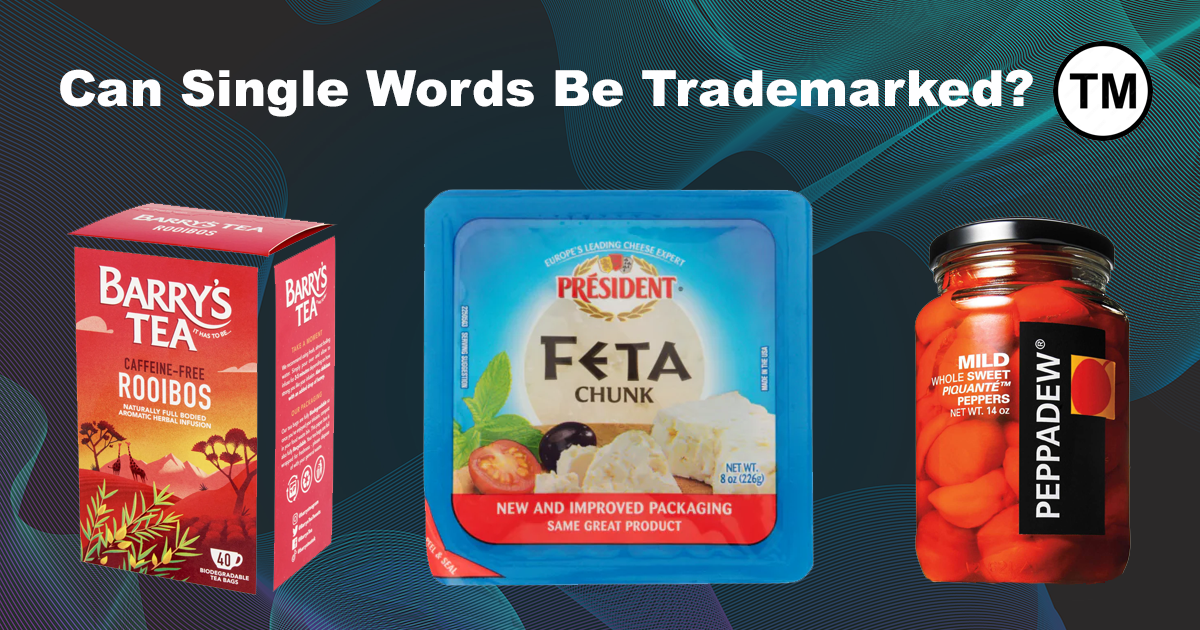

To look at an example of a trademarked word, let’s consider “Peppadew.” Once upon a time, these members of the capsicum family were just called “sweet bell peppers.” Nobody got excited about them until a man from South Africa started bottling them under the new name “Peppadew.”

Here’s the most fascinating part: now that everyone knows what a Peppadew is, hardly anyone realizes it’s essentially a sweet bell pepper, bottled using a specific recipe. You can bottle sweet bell peppers using the same method, but if you use the word “Peppadew” without permission, you’re infringing on their trademark.

Is it clever? You bet! And one South African is laughing all the way to the bank, likely humming a little Peppadew song.

One Big Trademark Fail

South Africa features in this story once again, but this time, the attempt to trademark a word didn’t go so well. In this case, someone took a big risk by trying to trademark a word they didn’t invent—they borrowed it. We’re talking about Rooibos tea.

The plant from which Rooibos tea is made originates in South Africa, and the tea has a distinctive red color. In Dutch, “rooi” means red, and “bos” means bush, so for centuries, this tea has been known as Rooibos, or red bush tea. As it started catching on in Europe for its caffeine-free benefits and pleasant flavor, someone in the US noticed the trend and trademarked the name “Rooibos” there.

As Rooibos grew in popularity, other importers tried selling it, only to discover they were breaching intellectual property laws. Fortunately, it was easily proven that Rooibos tea had always been called Rooibos, and the trademark dispute was promptly overturned.

Regional Fury

Have you ever sipped port wine, enjoyed feta cheese, or had a nice glass of Burgundy? A fierce debate erupted over these regional delicacies as imitation products began appearing worldwide.

Portugal objected to other countries marketing port wine under the name “Port,” which comes from the region where it was originally produced. Greece insisted that, as the originators of feta cheese, no one else should use the name “feta” for their cheese. Similarly, Burgundy residents argued that no imitation wine should be called after their region, and the list goes on.

This debate is still ongoing, and you may sometimes see compromise names like “Danish-style Feta.”

Can You Trademark a Word Everyone Already Uses?

If you’re hoping to become an overnight millionaire by trademarking the word “and” or some other common word, I’ve got bad news: it’s not going to happen. To trademark something, you must prove you invented or created it and that it uniquely identifies your goods or services.

Intellectual property rights can only be obtained for something distinctive and original, not for words in common use. Ideally, if you invent a great word, you should also trademark it. This way, you have full legal protection if someone tries to steal it. Ever wondered why companies often deliberately misspell words when branding a product? Now you know the answer! If it’s different and you were the first to think of it, it can become your intellectual property.

Using Common Words or Phrases as a Trademark

Here’s something cool: if you have a distinctive product, you can take an ordinary word or phrase and turn it into a trademark. The catch? An unrelated product can use the same word or phrase without breaching trademark law, as long as it’s for a completely different type of product.

Different Types of Intellectual Property

- Invented Words: If you invented a word, it’s yours—so long as you can prove you were the first to use it and that it uniquely identifies your goods or services.

- Trademarks: You can borrow a word and apply it to a specific product, registering it as a trademark. While this differs from copyright, the effects are similar. However, someone else could use the same word for a different product.

- Patents: Patents protect inventions from being copied. If you invented a new device called a “Fun-o-Meter” and patented it along with your invented word, no one else could use that word in connection with the patented device.

In Conclusion: Can You Trademark a Word?

Yes, you can! Just make sure it’s a new word, and that you have proof you created it and that it uniquely identifies your goods or services.