Writing Advice for Older Freelance Writers

Writing doesn’t suffer from quite the same age bias as other media occupations, but there is sometimes a tendency to favor younger writers over older writers. Why? Because younger writers are viewed as having a longer career ahead of them (which means more money for the publisher). Also, the sad truth is that younger writers are viewed as more “marketable.” They look better on book jackets, in magazine pieces, and in TV interviews. They also may be willing to work an absurd amount to break into the business. And, let’s face it, our culture is youth-obsessed. Those “Who to watch under 30,” lists and articles about the teenage wunderkinds sell magazines and fill news hours.

Despite this bias, there is still a chance for older writers to break in and make money. A great story or book is still valuable to a publisher, even if the author has one foot in the grave. Publishing is still a business whose object is to make money and a great book equals money, regardless of the author’s age. That’s the first thing an older writer needs to do and it’s fully within your control: Write the best story or book that you possibly can. Make it impossible for them to say no, no matter how old you are. Beyond that, you don’t want to handicap yourself any more than necessary. Here are some tips to skirt the age bias in publishing.

Don’t mention your age unless asked

Don’t bring it up in your query letter. Don’t send a picture of yourself. Most agents and editors will not admit to an age bias, but if you put it right there in front of them you may trigger their unintentional bias against you. Let your manuscript do the talking.

Don’t mention that you are “retired”

You may have taken up writing in your retirement, but don’t mention that in a query letter. You don’t want an agent or publisher to think of you as old, or as someone treats writing as a hobby. The only time retirement should be mentioned is if it’s relevant, but even then you should try to find a way to avoid it. For example, if you’re written a book about a Navy Seal and you are a retired Navy Seal, you might want to mention that, but rather than saying you are a “retired Navy Seal,” refer to yourself as a “former Navy Seal.”

Don’t mention your limitations

Publishers and agents need people who can get out there and help promote their books. If you have limitations that make that difficult, don’t bring it up until they are so in love with your manuscript that it won’t matter. If you aren’t technologically savvy, don’t bring that up, either, and work to correct it. Publishers expect you to be conversant in the world of Twitter, Facebook, email, and the like, and admitting that you aren’t isn’t a badge of honor, it’s a strike against you.

Draw on your experience and maturity

If you’ve spent any time in the working world, you should have a good idea of how to conduct professional conversations and write professional correspondence. You should be able to turn in projects on time and return calls promptly. You should be able to proofread and turn in error-free work. Not to say that younger writers can’t do these things, but older writers know how businesses work and “how to play the game.” Publishers like writers who are professional, prompt, and reliable.

Don’t date yourself

Along with not mentioning your age outright, don’t make reference to anything that might allow an agent or editor to figure it out. Don’t say, “I spent thirty years with XYZ Corp,” or, “I served in Korea.” Anyone with a brain can figure your probable age from that. Querying isn’t like writing a resume. Publishers don’t need your dates of employment. Leave anything that can date you out of it.

Don’t lie

While you don’t want to put a number on yourself early in the process, you don’t want to lie, either. If someone asks you directly about your age, fess up. The truth will always come out and you’ll be in trouble if you’ve fudged. Chances are, though, that if they’re asking about your age, they’ve already read the book and are seriously interested. Age matters less when the agent or editor feels like there is a salable project in the room. It’s that whole money thing, again.

Demonstrate commitment

While there are plenty of one-hit authors, publishers are usually looking for writers who are committed to producing multiple books. While this may be your first book, don’t mention it. A publisher can read between the lines and know that you’ve never been published if you don’t mention publishing credits, but you don’t need to say, “This is the first thing I’ve ever tried to write, it took me twenty years, and I feel like I’ve left it all on the table. This is my one great masterpiece.” Try to get some stories published in magazines or win some awards for other work to demonstrate that you’re active in the craft. You could also mention that this book is the first in a projected series (if it’s true).

Stay away from projects that scream, “Senior Citizen”

Unfortunately, memoirs and family histories not only give away your age but are often pegged as one hit wonders, if they’re a hit at all. The agent or editor sees these and thinks, “This person just wants to see this one project published before they die. They’re not a serious author.” Worse, the history or memoir that seems momentous to you is seen by the agent or editor as ho-hum. Unless your memoir or history is about something truly spectacular, you’ll probably want to stick with self-publishing for that.

Older writers can certainly break in, but they have to first write a book or story that is beyond reproach. Give a publisher something valuable and age starts to matter much less. Beyond that, though, it can’t hurt to keep your age out of the process for as long as possible. You don’t want someone to write you off before they even read your work. Sure, we should all be judged solely on our work, but it’s a sad truth that you have to outwit those who carry a bias against older writers.

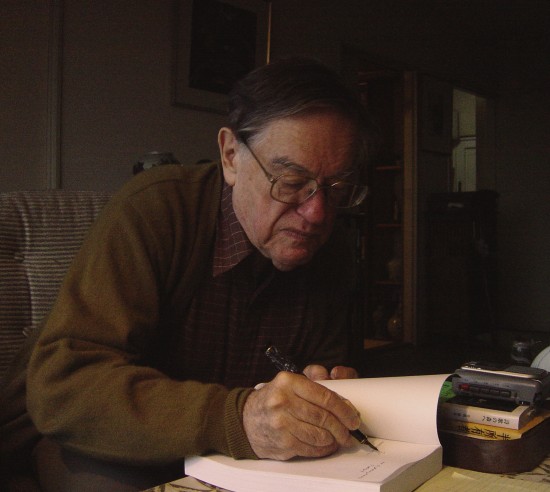

(Photo courtesy of Aurelio Asiain)